An exclusive Truthout investigation – released today on a day of national protest against police brutality – reveals that the City of Chicago fails to recognize, let alone sanction, police guilty of repeated episodes of violence, including the shooting deaths of unarmed civilians.

Ortiz Glaze, who had no criminal record and was unarmed, was running away with his back to police, when officers fired multiple shots at him, hitting him twice. (Photo: Alison Flowers)

Ortiz Glaze, who had no criminal record and was unarmed, was running away with his back to police, when officers fired multiple shots at him, hitting him twice. (Photo: Alison Flowers)

This story could not have been published without the support of readers like you. Click here to make a tax-deductible donation to Truthout and fund more stories like it!

On a clear, warm April day in 2013, a 35-year-old father of two, Ortiz Glaze, was manning a grill in his South Chicago neighborhood. He was cooking seafood, chicken and potatoes for scores of guests, including kids, in a parking lot. The barbecue, which stretched from day to night, was to commemorate his friend who had recently died from a shooting.

A group of Chicago police officers pulled up to the party, some wearing plain clothes and arriving in unmarked cars.

What happened next is where the stories differ. Police officers say Glaze was holding a cup appearing to contain alcohol, was ignoring orders and was gesturing to his waistband where Officer Louis Garcia and his partner, Officer Jeffrey Jones, say they believed he stowed a gun.

The other version is one corroborated by witnesses – that Jones fired into the crowd upon approach, causing everyone, including Glaze, to run away.

“The police are authorized to use force in ways that no other citizen is authorized to act . . . Police are rewarded for exercising force.”

From there, the following facts are not in dispute: Glaze, who had no criminal record, was unarmed. No gun was recovered. And while he was running away with his back to police, Jones and Garcia fired multiple shots at him, hitting him twice.

Glaze lived to tell his story.

“I laid there scared,” Glaze said of the moment when the bullets hit him. “Then he stood over me with his gun. I didn’t know if he was going to shoot at me again.”

When Glaze fell to the ground, his left arm and thigh wounded, Garcia handcuffed his right hand to his belt loop, arrested him and sent him to the hospital for treatment.

“My arm was a jangle,” Glaze said, pointing to the scar on his arm and the surgical plate beneath his flesh.

The officers fingerprinted Glaze, handcuffed his good hand to his hospital bed and used patient restraints to tie down his foot to the bed rail. They interrogated him.

After the shooting, a felony review unit at the Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office did not charge Glaze. The officers instead pursued charges of lesser misdemeanor offenses, including aggravated assault and resisting and obstructing police.

At Glaze’s bench trial almost a year later, it was the word of five police officers against Glaze. The judge quickly acquitted him of the charges.

“The judge saw right through them,” Glaze said. “It lets you know that they was lying.”

“The data we have would suggest conditions of virtual impunity for abusive officers.”

Glaze filed a lawsuit last April suing the City of Chicago, the Chicago Police Department and a slew of named officers, including Jones and Garcia. The lawsuit claims police planted a silver cell phone on Glaze – what police say resembled a gun as he was running – to justify their shooting. The device did not show up during an initial inventory report of Glaze’s belongings, according to the lawsuit. Chicago Police, on behalf of the department and named officers in this story, did not respond to Truthout’s requests for comment.

Unemployed, today Glaze keeps to himself and doesn’t go out much.

“I’m not the person like I was,” he said. “I’m just not really coming back around. Only time I can kick it is when I’m out of town. When I’m in Chicago, I can’t be myself.”

“Quasi-Military Organizations”

In 2013, Glaze was one of 43 people Chicago Police shot that year. Thirteen were killed, according to the City of Chicago Independent Police Review Authority (IPRA), the agency that reviews officer-involved shootings. IPRA did not respond to Truthout’s requests for comment.

“Police departments are quasi-military organizations,” said Art Lurigio, a criminologist and clinical psychologist who teaches at Loyola University. “The police are authorized to use force in ways that no other citizen is authorized to act.”

“The officer repeatedly called Mr. Johnson a n-gger” and “threatened to kill Mr. Johnson.”

The officer who shot at Glaze multiple times – Louis Garcia – has shot before. A May 2006 news release from the Chicago Police Department shows Garcia and his former partner, Martin Teresi, shot an armed offender in 2005. The Chicago Police Department awarded the pair the Superintendent’s Award of Valor for the shooting.

“Police are rewarded for exercising force and sometimes engaging in violent behaviors, including shooting at the suspects, including shooting dead the suspects, including tasing the suspects,” Lurigio said. “They are not credited for performance that’s passive.”

According to a new report by Chicago organization We Charge Genocide, which will be presented to the United Nations Committee Against Torture this November, more than 75 percent of those shot by Chicago Police over the last five years have been black people. African-Americans are more than 10 times likely to be shot by police than white people, IPRA data show.

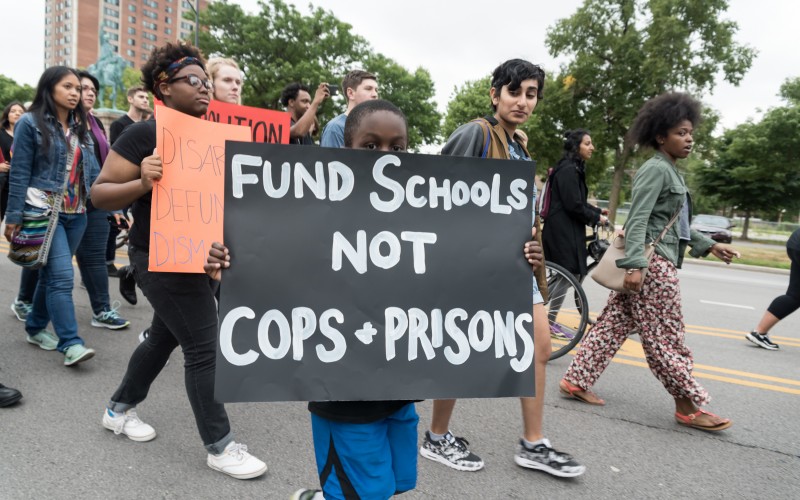

Protesters rally in Chicago in reaction to the shooting of Michael Brown. (Photo: Alison Flowers)

Protesters rally in Chicago in reaction to the shooting of Michael Brown. (Photo: Alison Flowers)

(Photo: Alison Flowers)

(Photo: Alison Flowers)

(Photo: Alison Flowers)A two-month investigation by Truthout delved into police shootings and misconduct complaints in Chicago, uncovering several key facts that raise questions about deadly force and police impunity.

(Photo: Alison Flowers)A two-month investigation by Truthout delved into police shootings and misconduct complaints in Chicago, uncovering several key facts that raise questions about deadly force and police impunity.

The investigation matched and analyzed data of officers with a high volume of historic misconduct complaints with police unit designations and current City of Chicago employee and budgetary public data. Alongside researching public documents, such as legal complaints and police news releases, the investigation was able to track the position of repeat alleged abusers still on the force and study the city’s investment in their conduct by way of salary, overtime pay and settlements.

To identify police shooters in controversial cases, Truthout cross-referenced media accounts naming victims with corresponding civil suits naming officers, screening hundreds of documents.

Out of the approximately 12,000 officers on the Chicago force between 2001 and 2006, most officers saw between zero and two misconduct complaints.

Reporters also interviewed victims of police brutality, criminologists, lawyers and a retired police officer, in addition to Jamie Kalven of the Invisible Institute, a Chicago-based journalistic production company, which led the seven-year battle to make misconduct complaint data public.

Two Freedom of Information Act requests submitted to the Chicago Police Department for Tactical Response Reports – the primary source document created by Chicago Police in any instance involving an officer’s firearm discharge – were rejected despite narrowing the request to six specific officers and three specific dates and locations.

The investigation found:

-At least 21 Chicago police officers are currently serving on the force, some with honors, after shooting citizens under highly questionable circumstances, resulting in at least $30.2 million in taxpayer-funded City of Chicago settlements thus far.

-Six officers who have shot and killed civilians also have a large volume of unpenalized complaints of misconduct.

-At least 500 Chicago police officers with more than 10 misconduct complaints over a five-year period (2001-2006) are still serving on the force. Their combined salary is $42.5 million dollars.

-Four lieutenants, the director and an organizer of the Chicago Alternative Policing Strategy (CAPS), 55 detectives, a field training officer and 69 sergeants are among the 500 Chicago police officers with more than 10 misconduct complaints over the five-year period.

-Police officer Raymond Piwnicki, now a detective, had the highest number of complaints in the five-year period, with 55 misconduct complaints and zero penalties. Piwnicki was awarded the Superintendent’s Award of Valor in 2013, for a shooting in which he is now a defendant in a civil suit that cites his “deliberate indifference” to a fellow officer’s deadly force.

-More than 60 of the 662 police officers with at least 10 misconduct complaints hailed from the Special Operations Section, responsible for 1,311 complaints in the five years of data alone. An elite citywide unit tasked with drug and gang investigations, Special Operations was disbanded in 2007 amidst multiple corruption scandals resulting in not only criminal charges of armed robbery, aggravated kidnapping and home invasion among seven of its former members – of which two are in jail – but a guilty plea in a murder for hire scheme. It was replaced by the Mobile Strike Force one year after Special Operations was disbanded, in the same unit headquarters, with the same orders, and many of the same officers. Disbanded in 2011, Mayor Rahm Emanuel reactivated Mobile Strike Force in 2013 with orders to “smother outbreaks of violence,” according to the Chicago Sun-Times.

-From 2002 to 2008, out of 90 excessive force complaints, specifically denoting improper “weapon, use/display of,” all but eight were dismissed, with only five noting the violation. In this time period, a paralyzed man, Cornelius Ware, was shot and killed by Officer Anthony Blake, whose record denoted a weapon complaint as “unfounded.” The City of Chicago later awarded Ware’s family a settlement of $5.25 million.

-During the 2001 to 2006 span, more than three dozen police officers had 29 or more misconduct complaints on their records, more than double the number of complaints that recently indicted Chicago Police commander Glenn Evans accumulated during the same period.

“Full-Time Gangsters”

Martin Teresi, former partner of Louis Garcia, who shot Ortiz Glaze, accumulated 35 misconduct complaints from 2001 to 2006, by the time he and Garcia received their 2006 award. Those complaints resulted in zero penalties.

“The data we have would suggest conditions of virtual impunity for abusive officers,” said writer and human rights activist Jamie Kalven of the Invisible Institute. “That means full-time gangsters. That means utterly cruel individuals who get off on humiliating African-Americans or women. A small amount on the force, but a huge impact.”

Among the complaints against Teresi are two different excessive force complaints involving the teen children of black officers, one of whom suffered a fractured nose and two broken ribs, according to the complaint, which was settled out of court.

The Chicago Police Department’s track record of rarely delivering meaningful penalties for misconduct signals a culture in which incidents of fatal force are nearly always deemed justifiable.

Since the 2001-2006 time period, Teresi was named in another excessive force complaint involving minors, and in the settlement of Mario Navia Jr., whose complaint describes him being pulled over without reason and quickly arrested, pepper-sprayed and beaten by six officers who used a nightstick that left a gash in his head requiring multiple staples.

In 2013, the case settled. In 2014, Teresi received the Superintendent’s Award of Valor from Chicago Police, for another incident involving the discharge of his weapon, according to the department’s news release.

Garcia’s record from 2001 to 2006 did not reach the baseline of surpassing 10 complaints for inclusion in the repeat misconduct complaint list. Yet civil suits against Garcia – three in progress, including that of Glaze – mark a consistent history of extreme excessive force prior to Glaze’s shooting.

In 2005, Ronald Johnson, from Chicago’s South Side, accused Garcia, seven other officers and the City of Chicago in a lawsuit of excessive force, false arrest, unreasonable search and seizure, malicious prosecution and hate crime.

The city does not track shootings, perform pattern analyses of shootings or examine officers and units with high numbers of misconduct complaints in a short period of time.

Garcia is described as solely responsible for the hate crime of “placing Johnson in a choke-hold which cut off his breathing. The officer repeatedly called Mr. Johnson a n-gger” and “threatened to kill Mr. Johnson,” according to the lawsuit.

Johnson’s case settled for $99,000.

Five years later, a charge of excessive force was again filed against Garcia. The lawsuit, made by disabled 52-year-old Ruben Sanchez, describes Garcia as emerging from an unmarked police car, gun drawn, in front of Sanchez’s home. Ordered to lie on his stomach, Sanchez explained he could not comply given a recent surgery. “Garcia punched Sanchez in the mouth,” the civil suit alleges, further elaborating, “When Sanchez, now bloodied, insisted he could not lie on his stomach, Garcia again punched Sanchez in the mouth and forcibly threw Sanchez to the ground.”

Three years after the Sanchez incident, Garcia and Jeffrey Jones shot at Ortiz Glaze.

“A Biopsy of the City’s Accountability System”

Writer and human rights activist Jamie Kalven said the now-public Chicago Police data show “dramatic portraits” of individual officers, “but it’s also a biopsy of the city’s accountability system.” (Photo: Patricia Evans)Earlier this year, a watershed moment in police accountability occurred, opening a small window that has shed light on Chicago Police patterns and practices.

Writer and human rights activist Jamie Kalven said the now-public Chicago Police data show “dramatic portraits” of individual officers, “but it’s also a biopsy of the city’s accountability system.” (Photo: Patricia Evans)Earlier this year, a watershed moment in police accountability occurred, opening a small window that has shed light on Chicago Police patterns and practices.

In March, an Illinois appeals court ruled in Kalven v. Chicago that documents bearing on allegations of police misconduct are public information. In July, the City of Chicago released sets of documents long sought by lawyers and journalists.

The sunshine is thanks in large part to Jamie Kalven, who had previously become entangled, and later intervened, in a federal lawsuit where the police records had been at issue.

In the span of six months, Officer Gildardo Sierra shot three people – two of them fatally.

“The dramatic portraits that emerge are of individual officers, but it’s also a biopsy of the city’s accountability system,” Kalven said of the now-public police data. “There are patterns that jump out to you.”

Out of the approximately 12,000 officers on the Chicago force between 2001 and 2006, most officers saw between zero and two misconduct complaints, Kalven said. Another set of officers had between two and 10 complaints.

But where the data points blow the whistle is the 662 officers who individually account for 10 misconduct complaints or more – what Kalven calls the “repeater list.”

For this investigation, Truthout used Kalven’s recently released repeater list, among other public data.

Shootings

The Chicago Police Department’s track record of rarely delivering meaningful penalties for misconduct signals a culture in which incidents of fatal force are nearly always deemed justifiable, Truthout has found.

There is one notable exception: Police officer Dante Servin will, later this month, stand trial for shooting Rekia Boyd in the back of the head while off duty in 2012, killing her. Facing charges of involuntary manslaughter, reckless discharge of a firearm and reckless conduct, Servin is the first Chicago police officer in 15 years to stand in a criminal trial.

But among the many remaining officers who have likewise shot civilians – deemed justified under highly questionable circumstances – it is nearly impossible to track the consequences of such impunity.

A patrol car video shows Sierra walking in a semicircle around Farmer, lying face down on the ground wounded, before firing three shots into his back, killing him.

City agencies have shut out efforts to monitor the frequency of Chicago Police officer-involved shootings. Earlier this year, John Conroy, director of investigations at the DePaul Legal Clinic (and the journalist who helped expose the decades-long Chicago Police torture ring under former Commander Jon Burge), submitted several public information requests seeking records related to the frequency of police shootings. The Chicago Mayor’s Office, the Chicago Police Board and the City of Chicago Independent Police Review Authority all responded that no such records existed, while the Chicago Police Department turned over a cursory two-page document that illuminated little to nothing.

Kalven’s “biopsy” of city data – compiled after a long fight for information by civil rights lawyers – confirms that the city does not track shootings, perform pattern analyses of shootings or examine officers and units with high numbers of misconduct complaints in a short period of time.

Officer Gildardo Sierra

In 2011, Chicago Police Superintendent Garry McCarthy, speaking on the matter with the Chicago Tribune, confirmed the department did not maintain any internal system to track officers involved in multiple shootings. In the span of six months that same year, Officer Gildardo Sierra shot three people – two of them fatally.

Flint Farmer was the last of those shot by Sierra, who had been called on a domestic disturbance to Farmer’s Englewood location. When Sierra and his partner arrived, Farmer took off running. At the next block, Sierra, who later claimed he “feared for his life,” began shooting at Farmer, who was unarmed. Discharging his weapon a total of 16 times, Sierra hit Farmer with seven of his bullets. It was the final three shots that killed Farmer, according to the Cook County medical examiner.

A patrol car video shows Sierra walking in a semicircle around Farmer, lying face down on the ground wounded, before firing three shots into his back, killing him. The shots are illuminated in the video by muzzle flashes indicative of close range.

Farmer’s family settled their civil suit for $4.1 million.

A “good shooting” is when someone’s life was at risk, and a “bad shooting” is what the controversial Ferguson, Missouri, killing of unarmed teenager Michael Brown looks to be.

Yet Cook County State’s Attorney Anita Alvarez ruled the shooting justified. After a two-year investigation, county prosecutors concluded that evidence supported Sierra’s claim that he had acted in self-defense – after mistaking Farmer’s cellphone as a weapon.

“Not every mistake demands the action of the criminal justice system, even when the results are tragic,” Alvarez wrote in a letter to McCarthy.

Stripped of police powers, Sierra was transferred to the city’s 311 call center.

Near the beginning of his career on the force, Sierra had been awarded the Distinguished Service Award by the Fraternal Order of Police. At the City Council Finance Committee meeting in which the settlement was approved, Leslie Darling, an attorney for the City of Chicago, told council members Farmer’s shooting was in fact the eighth in which Sierra was involved.

City data lists Sierra as a police officer with a salary of $78,012.

Still on the Force

Truthout’s investigation identified a number of additional officers1 who have pulled the trigger in instances of highly controversial civilian deaths. Including officers already mentioned herein, the investigation identified that among officers currently serving on the force, there are at least:

- Five officers who shot and killed civilians from behind, with a record of more than 10 complaints in five years.

Among this group is Officer John Fitzgerald, who shot Aaron Harrison, a black 18-year-old, in 2007, after garnering 25 misconduct complaints between 2001 and 2006. A member of Special Operations, Fitzgerald was awarded the Superintendent’s Award of Valor in 2010, according to a Chicago Police Department news release, for the incident. The shooting was ruled justified by the City of Chicago Independent Police Review Authority, largely on the basis of Fitzgerald’s assertion Harrison was attempting to shoot him while running away, and a gun recovered on the scene. Multiple witnesses asserted Harrison was unarmed. In 2013, Harrison’s family’s civil suit settled for $8.5 million.

- Six officers with a record of more than 10 complaints in five years are named in lawsuits for their involvement in shootings, among them, Raymond Piwnicki, and Chris Hackett, who, according to witnesses, ran over 23-year-old Jamaal Moore.

Unarmed and attempting to flee from the officer and his partner following a car chase in Englewood and the resulting crash, Moore was then shot by Hackett’s partner Ruth Castelli two times at close range, once in the back. IPRA exonerated the officers despite both a patrol car dash cam video and a gas station surveillance video that contradict their account, according to a memorandum opinion and order by the judge in the subsequent civil suit, which settled for $1.25 million. From 2001 to 2006, Hackett garnered 15 misconduct complaints and zero penalties.

- Fourteen officers who fatally shot civilians, without a record of more than 10 misconduct complaints, 2001-2006, including Castelli and Phyllis Clinkscales who shot unarmed 17-year-old Robert Washington at such close range that residue and the muzzle imprint of her weapon were left on his skin.

The Chicago Police Department found the shooting justified within hours, and later ignored IPRA’s recommendation that Clinkscales be fired. In-depth Chicago Tribune reporting revealed many other salient facts surrounding the shooting in 2007. Yet city data lists Clinkscales as a police officer, with a salary of $83,706, and 2013 overtime earnings of $38,996.

Collis Underwood, who the City Council granted an honorific resolution this April for intervening in a potentially deadly domestic disturbance, fatally shot 23-year-old Xavier Ferguson twice in the chest following a traffic stop in 2010 while on patrol in the Mobile Strike Force. The officer asserted Ferguson “lunged” for his weapon. Ferguson’s family, who did not believe the young father of two would attempt to disarm an officer, filed a wrongful death suit. The jury ruled in Underwood’s favor. Another civil suit against him, with a charge of excessive force, is currently underway. According to the lawsuit, Underwood and his partner extensively beat Dennis Dixon, resulting in a “fractured hand that required surgery, a blunt head injury and multiple bruises/contusions.”

“We’re Not Dirty Harry”

Retired police sergeant and police psychology expert Richard Greenleaf says police officers talk about “good shootings” and “bad shootings” in such simple terms. (Photo: Roark Johnson)Outside of Chicago, Richard Greenleaf, a retired Albuquerque police sergeant, teaches criminology at Elmhurst College. He is an expert in police psychology.

Retired police sergeant and police psychology expert Richard Greenleaf says police officers talk about “good shootings” and “bad shootings” in such simple terms. (Photo: Roark Johnson)Outside of Chicago, Richard Greenleaf, a retired Albuquerque police sergeant, teaches criminology at Elmhurst College. He is an expert in police psychology.

Citing the split-second, life-or-death dynamic police operate in, Greenleaf empathizes with police officers who have pulled the trigger. He is one of them.

In 1981, Greenleaf shot and killed an armed robber who was out on bond for an alleged stabbing. The guy turned his gun on him; Greenleaf responded by firing three rounds, hitting him twice – once in the chest, and once in the lower groin.

After the incident, he got three days off with pay and had to visit the police counselor. Later, when psychological services had an opening, he became that counselor. Greenleaf holds a graduate degree in counseling and a PhD in sociology.

“I’ve been strip-searched in the middle of the street.”

Police, who Greenleaf described as being on high alert and in a constant mindset of danger, talk about “good shootings” and “bad shootings” in such simple terms internally. A “good shooting” is when someone’s life was at risk, and a “bad shooting” is what the controversial Ferguson, Missouri, killing of unarmed teenager Michael Brown looks to be, Greenleaf explained.

Greenleaf witnessed abusive force during his seven years as an officer in Albuquerque.

“There are departments that have histories of not just having bad apples, but a batch of rotten apples,” Greenleaf said. “But the number of shootings alone does not necessarily mean that the department is corrupt or has bad officers.”

Today, Greenleaf says he steers his students, some of them police officers themselves, away from caricatures of law enforcement like Dirty Harry, John Wayne or even Superman.

But when he speaks of taking a human life, his voice lowers and softens.

“I wish it never happened,” Greenleaf said. “I wish he had lived. But I was in fear of my life.”

Whether citizens are actually guilty of the perceived offense that leads to apprehension is not what shakes their sense of justice.

However, the aftermath of police shootings in Chicago, Truthout found, contradicts this good shooting/bad shooting dichotomy, with the grisly details behind “good shootings” emerging through video footage, media accounts and civil lawsuits where victims and their families have garnered large settlements. Some of these shootings have not only been “justified” by the Chicago Police Department, the Independent Police Review Authority and Cook County State’s Attorney Anita Alvarez – but also rewarded. What remains unknown is the process by which they are judged internally and the systemic underpinnings behind how they come to be praised.

At the same time, no government agency consistently tracks “good shootings” and “bad shootings,” among the estimated 1,000 police shootings across the country annually. One of the only attempts includes self-reporting from a fraction of the nation’s law enforcement agencies to the FBI’s data on “justifiable homicides.” A journalist and publisher launched another attempt in 2012, the crowdsourcing project “Fatal Encounters.” The project seeks to create an impartial, comprehensive and searchable national database of people killed during interactions with law enforcement.

“For Their Reputation”

The City of Chicago Independent Police Review Authority has conducted 272 investigations, spanning from shootings to alleged police violence over the last five years. Officers are rarely disciplined. In 22 complaints, there was no investigation.

Still, many incidents of police misconduct never make it to IPRA’s books because the alleged victims do not complain, leaving only anecdotal evidence recounted to those who will listen. Truthout sought police records to confirm the following accounts – just a few of the many incidents that take place on a daily basis in the city – but the Chicago Police Department did not respond to these Freedom of Information Act requests. (2)

A 53-year-old South Sider, Percy McGill, has been in and out of prison on drug charges. He claims to be physically handled by police every day.

“They throw you against the car and search you with no reason,” McGill said. “I mean, you don’t have to be doing anything. You can be just walking down the street, going to the store. If they see you, they’re going to stop you and search you.”

Andre Wilson, a 51-year-old West Sider, is also no stranger to the criminal justice system, a fact that he believes has caused police to discriminate against him even when he is clean on the streets.

“I’ve been strip-searched in the middle of the street,” Wilson said. “I think that’s really degrading.”

On one occasion, he flicked a bag of heroin when he saw police coming after him. The bag was never found, “so they found something for me,” Wilson said.

Cory Lyles, a 43-year-old father of two from the West Side, does not have a criminal history like McGill or Wilson, but found himself handcuffed to a wall at a police station for hours after being mistaken for someone else.

Once released, Lyles returned to his car to find it doused in Hennessey, he claims. He tried to tell his story to a “white-shirt” back at the station, but never put in a complaint because he felt intimidated by the officers.

Stanley Davis, 45, a West Sider who had only been home from prison for 40 days when he spoke to Truthout in early October, has spent more time incarcerated than out free, with seven incarcerations totaling 26 years. He admits he has hustled, but asserts innocence in three of the crimes for which he was imprisoned.

There is not always malice behind the misconduct – just the incentive to meet a quota.

Davis experienced police violence around the 2012 incident that led to his most recent incarceration, he says. After being stopped and forced to the ground by two officers, a third officer jumped out of his car and came down on his back with his knee, according to Davis.

“It felt like he pushed my back into the earth,” Davis said. “I felt that pain for some time, but wasn’t nothing broke.”

Whether citizens are actually guilty of the perceived offense that leads to apprehension is not what shakes their sense of justice, according to Art Lurigio, criminologist and clinical psychologist at Loyola University.

“More important to citizens than the actual outcome is how they were treated,” Lurigio said. “This ain’t a fair fight anymore.”

After Davis’ forceful shakedown, he couldn’t remember the names of the officers involved and says he never filed a complaint.

“These guys, they use aliases,” Davis said. “They use these Rambo names. They get people conditioned to them Rambo names, so it kind of throw everybody off. This one, he called hisself ‘Thirsty.'”

To Davis, there is not always malice behind the misconduct – just the incentive to meet a quota.

“They are destroying a human life,” Davis said. “Take your freedom away and put you in a situation away from your children, away from your family, just for their status. For their reputation.”

Footnotes

1. The additional police shooters below emerged in the investigation. They did not respond to requests from TruthOut for comment.

- Officer Rick Caballero who shot Ben Romaine, who was driving away from Caballero, and killed him; later awarded the Superintendent Award for Valor for the incident, which settled in a civil suit

- Officer Robert Haile who shot and killed Lazuanjo Brooks multiple times and in the back; the shooting settled in a civil suit

- Sergeant David Rodriguez who shot Herbert Becker at close range; the shooting settled in a civil suit

- Officer Vilma Argueta who shot and killed 19-year-old George Lash on the Chicago Transit Authority; receiving an award for the incident, which was voluntarily dismissed by the Lash family lawyers in a civil suit

- Officer Darren Wright who shot and killed 17-year-old Corey Harris in the back; the shooting settled in a civil suit

- Officers Shawn Lawryn and Juan Martinez, who shot and killed Eseau Castellanos; in a civil suit currently underway, the complaint highlights ballistics reports contradicting the officers’ accounts

- Officer Michael St. Clair who shot William Hope multiple times in the chest in broad daylight, while sitting in his car; the shooting later settled

2. CPD did respond to that FOIA request after the deadline with incomplete information and a request that we narrow our search.