On June 8, 2016, three members of a We Charge Genocide working group, Real Community Accountability for People’s Safety (RCAPS) met with the Department of Justice. As part of their investigation into police use of deadly force in Chicago, the DOJ wanted to discuss The Counter-CAPS Report: The Community Engagement Arm of the Police State. Community policing is currently an important plank in proposals for criminal justice reform. Through our independent, collaborative and grassroots research, we found that community policing mobilizes a self-selecting group to work with police and insulate them from scrutiny. It’s a way to generate some support for and increase the legitimacy of the police, not a serious solution to problems with state violence.

We wrote the Counter-CAPS report to challenge the emerging common sense on police reform. In the past two years, the Obama administration has advocated community policing as a key part of the solution to the “Post-Ferguson” crisis of police legitimacy. When Obama traveled to Chicago to address the annual meeting of International Association of Chiefs of Police, he advocated community policing. Anticipating as much, a group of radical black organizations—the Workers Center for Racial Justice, the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement, and BYP 100, among others—organized “I Shocked the Sheriff,” a people’s congress and series of direct actions, to counter the ICAP meeting. A few days later, RCAPS released The Counter-CAPS Report as a complement to these actions and expression of the movement’s rejection of false solutions like community policing.

Our discussion with the DOJ was a continuation of this confrontation. We met with a DOJ lawyer and Scott Thomson, Chief of Camden County Police Department. Thomson is credited with using community policing to drive down the outsized crime rates of Camden, NJ, which, in 2012, held the infamous designation as the most violent and impoverished city in the United States. In May 2015, President Obama used Camden and its community policing programs as a backdrop to announce the findings of the post-Ferguson Commission on 21st Century Policing. Thomson has since become the president of the Police Executive Research Foundation, an influential reform-minded police association.

Of course, the reforms proposed by the Commission on 21st Century Policing and championed by people like Obama and Thomson are perfectly compatible with the aggressive policing that’s ostensibly being curtailed. Camden’s celebrated community policing operations, for example, exist alongside (and feed into) ubiquitous surveillance and intelligence gathering that enable police raids within criminalized and disinvested communities. Chicago’s community policing program—the oldest and largest of its kind in the nation—did nothing to prevent stop-and-frisk, off-the-books detention and interrogation, other abuses that have led to $521 million in settlements over the last decade; and a series of scandals that have tarnished (the already minimal) credibility of Chicago Police Department and existing oversight mechanisms.

Our Counter-CAPS Reports shows community policing can coexist with these aggressive police operations because it does not create meaningful public accountability over the police. Instead of creating some kind meaningful involvement of “the community” in the provisioning of “security,” community policing is a liberal euphemism that hides a nefarious purpose–the political work of the police to organize the population and produce order, not just enforce it.”

The unacknowledged politics of community politicking were quickly laid bare to us. During the summer of 2015, RCAPS members began observing regular meetings between police and community members. While these meetings are meant to involve the public in collaborative problem solving with the police, we found them to be places where police organize micro-local political power. At community policing meetings, officers set the agenda and determine the appropriate response. Working in concert with a volunteer beat facilitator (a quasi-official position often connected to aldermen), officers organize residents into block groups and phone trees to report “suspicious” behavior. They encourage residents to call the police for nearly any perceived problem they experience, including minor issues such as profanity–providing cover for aggressive policing of quality of life issues. They direct the residents to focus on “problem properties” and build the case for investigation or eviction through their consistent monitoring and reporting.

These programs reduce social problems—poverty, inequality, segregation, homelessness—and transform them into technical “quality of life” problems that can be redressed by police action. In mobilizing residents as intelligence collectors for the police and political advocates for a punitive criminal justice (http://home.chicagopolice.org/get-involved-with-caps/how-can-i-get-involved/become-a-court-advocate/), community policing enlists us in the work of our domination. In exchange for a meaningless “seat at the table” in the police precinct, we can become junior partners in the operations of our local police state.

In other words, community policing is being offered at this moment precisely because it offers the promise of blunting grievances of radical movements and co-opting some of their leaders. Within this context, radicals are repressed. Potentially rebellious groups—such as the ever-increasing surplus populations warehoused in prisons—are incapacitated. Moderates are accommodated. The loyal opposition—such as the liberal NGOs that routinely undercut the work of autonomous grassroots—are politically incorporated as junior partners of the political elite. The iron first and the velvet glove operate hand-in-hand to pacify restive populations and mollify rebellion.

With this research and analysis informing our comments, the members of RCAPS hesitated to offer Thomson and the DOJ lawyer the pat suggestions for “reform” that they desired. We do not want “better” policing. We want to transform the institutions that mediate disputes, restore victims, and rehabilitate and reintegrate people who cause harm. Instead, we asked them “act with courage” and recognize that community policing is part of the problem, not the part of the solution.

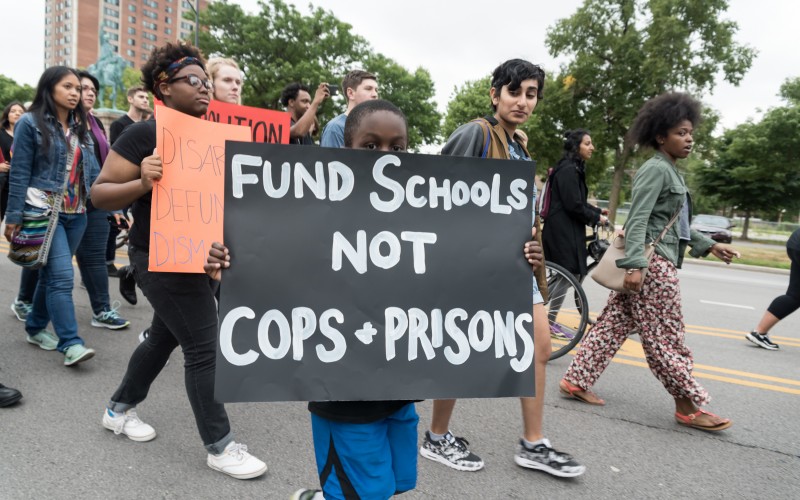

This refusal to offer suggested reforms is not an attempt to avoid the difficult work wielding political power. Instead, it reflects a radical analysis that sees policing as institution beyond reform. With this mind, our suggestions—a rejection of community of policing and reduction of police budget—are our non-reformist reforms that seek to transform the balance of power in Chicago to the benefit of the people.

At the end of the meeting, we left the DOJ lawyer and Thomson with the annotated bibliography appended to the end of this write up. The bibliography extends and elaborates the arguments we made to the DOJ, adding further weight and context to the findings of the RCAPS report. The bibliography starts with a series of critical perspective on community policing. These studies show the historical and practical affinities between community policing and counterinsurgency, dispelling the commonly held notion that community policing is a demilitarizing reform. Annie Laure Paradise’s dissertation takes this critique a step further, contrasting state security initiatives with autonomous grassroots projects for community safety. This heavily theorized work provides some context to our refusal to engage in the reform process. The DOJ wants a better, more professional, and re-legimitatized policing. RCAPS, We Charge Genocide and similar groups are working to building alternative institutions.

From here, the annotated bibliography covers relevant empirical research on community policing, with specific focus on Chicago. This work questions the efficacy of community policing: casting doubt on its impact on crime, its ability to meaningfully involve the community, and officer’s faith in the strategy. The final two articles further support our findings about gentrification and detail the shift of community development from a largely grassroots effort to a much smaller and fragmented one led by professionalized groups. This historical context provides interesting parallels to and perspective on the present.

We share this experience and these sources to document Chicago’s resistance to community policing. We call on other groups in similar struggles to question community policing and resist the larger efforts to pacify our movement.

Annotated Bibliography on Community Policing

A Supplement to The Counter-CAPS Report

Critical Perspectives

A critique of the concept of militarization that argues community policing is compatible with the more punitive policing strategies associated with “militarized” police. A challenge to the notion that community policing is a viable way to reform policing post-Ferguson.

Williams, K. (2011). The other side of the COIN: Counterinsurgency and community policing. Interface, 3(1), 81-117.

An analysis of community policing as the domestic application of counterinsurgency or the political work of law enforcement to rebuild legitimacy of the state. In these operations, police will often work with and through faith leaders and civic to channel and control opposition. Community policing does not build “good governance.” It is the work of public diplomacy and outreach that complements the use of state’s repressive force.

This heavily theorized PhD dissertation contrasts autonomous projects for community safety against state security initiatives. Grounded in a feminist politics of care, projects for community safety construct “common” relations of social reproduction, providing ways to address social needs, share information, and link communities. These efforts represent a sharp contrast to community policing, theorized as a technique of state power conditioned by colonial histories (such as counterinsurgency) that operates today to manage precarity and disrupt challenges to the racialized and gendered relations that enable the exploitation of labor and accumulation of capital to proceed.

Relevant Empirical and Historical Studies

MacDonald, J. M. (2002). The effectiveness of community policing in reducing urban violence. Crime & Delinquency, 48(4), 592-618.

A statistical analysis of homicide and robbery in164 American cities that finds community policing had little effect on the decline in violent crime.

Skogan, W. G. (2006). Police and community in Chicago: A tale of three cities. New York: Oxford University Press.

The culmination of twelve years of study, the definitive account of CAPS concludes that the program failed to produce meaningful community control over police. Officers retain control of decision making and agenda-setting. Proportional to population, participation in beat meetings is abysmally low, typically less than half a percent of the neighborhood. The result is depoliticized representation: limited participation without binding votes or any mechanism for public accountability.

Survey of CPD officers that found ambivalent opinions about CAPS and doubts concerning its impact on crime rates.

Nyden, P. W., Edlynn, E., & Davis, J. (2006). The differential impact of gentrification on communities in Chicago. Chicago, IL: Loyola University Chicago Center for Urban Research and Learning.

This focus group study on the impact of gentrification finds that many respondents contend that crime and community policing are being manipulated to control or displace low-income residents. Residents community areas where tensions around gentrification are high (Uptown and West Town/Humboldt Park) felt that CAPS is promoting the power of wealthier, incoming residents, while disempowering the less affluent, current residents. Notably, the research team did not explicitly ask about CAPS. Instead, the issue emerged organically as an unexpected finding of the study.

Betancur, J. J., & Gills, D. C. (2004). Community Development in Chicago: From Harold Washington to Richard M. Daley. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 594(1), 92-108.

This article details the transformation of community development in Chicago from a predominately grass roots movement for social change to a much smaller and fragmented one led by professionalized groups. Community development has been absconded to serve the interests of progrowth and corporate interests rather than used as a tool to promote fairness, access, and equity in low-income neighborhoods. As part of this shift, the rise of community policing empowered most conservative community elements to work with the police and criminalized poverty. In particular, community policing has changed the city’s approach to homelessness and youth, replacing social workers and individual focus on treatment and care with policing and an emphasis on risk management.